lost? HOME » SUPPLEMENTS » BIBLIOGRAPHIA » DEE / RENAISSANCE / EMPIRE

The corners and straights of the earth shall be measured to the depth: and strange shall be the wonders that are creeping in to new worlds. Time shall be altered, with the difference of day and night. All things have grown almost to their fullness

dee / renaissance / empire

JOHN DEE: Christian Cabalist

New factual material is constantly turning up; many scholars are trying to assess his scientific thought; the old prejudices against him as a ludicrous figure still subsist, though very much diminished in force as it becomes more and more apparent that Dee had contacts with nearly everyone of importance in the age, that his missionary journey to Bohemia had enormous repercussions, that, in short, the life and work fo John Dee constitute a problem the solution of which is not yet in sight. [OP, 79]

Dee’s first period (1558-83): The Leader of the Elizabethan Renaissance

JD (1527-1608) was the son of an official at the court of Henry VIII.

He was of Welsh descent, and believed himself to be descended from an ancient British prince, even claiming some relationship to the Tudors and to the queen herself. He associated himself intensely with the Arthurian, mythical, and mystical side of the Elizabethan idea of ‘British Empire’. [80]

Among the thousands of books in Dee’s library […] he had a considerable collection of Lullist works. He possessed the works of Pico della Mirandola and of Reuchlin. He owned several copies of Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia. He had the 1545 edition of the Latin version of Giorgi’s De harmonia mundi. There is no doubt that he was fully conversant with these works and with many others of similar tendency. Though such works may have formed the core of Dee’s library and filled the centre of his mind, that library and that mind also included a vast wealth of scientific knowledge of all kinds, and of literary and historical material. It was the library of a man of the Renaissance, bent on assimilating the whole realm of knowledge available in his time.

This library was at the disposal of friends and students. Here came courtiers and poets, like Sir Philip Sidney, navigators and mathematicians, historians and antiquaries, all learning from Dee’s stores.

manifesto (the preface)

The manifesto of Dee’s movement was his preface to Henry Billingsley’s translation of Euclid, which was published in 1570.

With the opening invocation to ‘Divine Plato’ we are at once in the world of ‘Renaissance Neoplatonism’. The subject of the Preface is the importance of number and of mathematical sciences, and this is confirmed by quotation from one Pico della Mirandola’s Mathematical Conclusions: ‘By number, a way is had, to the searching out and understanding of every thyng, hable to be knowen.’

And Dee’s Neoplatonism is associated with Renaissance Cabala, for the outline of the Preface is based on Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia on three worlds.

The tendency of the movement towards concentration on number as the key to the universe, which is apparent in Agrippa and in Giorgi, and which Reuchlin had accentuated through his emphatic association of Pythagoreanism with Cabala, is carried forward by Dee in a yet more intensely ‘mathematical’ direction.

on empire

Dee was not only an enthusiast for scientific and mathematical studies, in the strange contexts in which he saw them. He wished to use such studies for the advantage of his countrymen and for the expansion of Elizabethan England. Dee had a politico-religious programme and it was concerned with the imperial destiny of Queen Elizabeth I.

It [Elizabethan imperialism] was not only concerned with national expansion in the literal sense, but carried with it the religious associations of the imperial tradition, applying those to Elizabeth as the representative of ‘imperial reform’, of a purified and reformed religion to be expressed and propagated through a reformed empire, the empire of the Tudors with their mythical ‘British’ associations.

The glorification of the Tudor monarchy as a religious imperial institution rested on the fact that the Tudor reform had dispensed with the Pope and made the monarch supreme in both church and state. This basic political fact was draped in the mystique of ‘ancient British monarchy’, wit its Arthurian associations, represented by the Tudors in their capacity as an ancient British line, of supposed Arthurian descent, returned to power and supporting a pure British Church, defended by a religious chivalry from the evil powers (evil according to this point of view) of Hispano-Papal attempts at universal domination.

Though these ideas were inherent in the Tudor myth, Dee had a great deal to do with enhancing and expanding them. Believing himself to be of ancient British royal descent, he identified completely with the British imperial myth around Elizabeth I and did all in his power to support it.

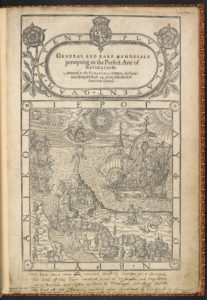

Dee’s views on the British-imperial destiny of Queen Elizabeth I are set out in his General and rare memorials pertayning to the Perfect art of navigation (1577). Expansion of the navy and Elizabethan expansion at sea were connected in his mind with vast ideas concerning the lands to which (in his view) Elizabeth might lay claim through her mythical descent from King Arthur. Dee’s ‘British imperialism’ is bound up with the ‘British History’ recounted by Geoffrey of Monmouth, based on the myth of the hypothetical descent of British monarchs from Brut, supposedly of Trojan origin, and therefore connecting with Virgil and the Roman imperial myth. Arthur was the supposed descendent of Brut, and was the chief religious and mystical exemplar of sacred British imperial Christianity.

In the General and rare memorials there is a complicated print based on a drawing by Dee’s own hand, of Elizabeth sailing in a ship labelled ‘Europa’ with the moral that Britain is to grow strong at sea, so that through her ‘Imperial Monarchy’ she may perhaps become the pilot of all Christendom. This ‘British Hieroglyphick’, as Dee calls the design, should be held in mind at the same time as the Monas hieroglyphica, as representing a politico-religious expression of the monas in the direction of a ‘British imperial’ idea.

On the establishment of a new nomos of the earth based on a new relationship between land and sea, see Schmitt [notes here]

From ‘John Dee and the Mechanicians’ in John Dee: The Worlds of an Elizabethan Magus, Peter French:

As one might expect, Dee’s enthusiasm for promoting English exploratory voyages was inspired by a number of motives. First, he hoped to find a way to the East, for traditionally (and he accepted this tradition) it represented one of the great repositories of occult knowledge. Second, John Dee had an apocalyptic vision of England’s future in which he perceived the formation of an ‘Incomparable BRYTISH IMPIRE’ – both religious and political – with Elizabeth as empress. The possible material wealth to be gained for the country through exploration was not overlooked, but it was only a secondary factor.

[…]

French’s reading of the print:

inspired melancholia

In what light would this deep student of the sciences of number, this prophetic interpreter of British history, have been seen, both by himself and by his contemporaries?

I would suggest that the contemporary role which would exactly fit Dee would be that of the ‘inspired melancholic’. According to Agrippa, and as portrayed by Dürer in the famous engraving, the inspired melancholic was a Saturnian, immersed in those sciences of number which could lead their devotees into great depths of insight. Surely Dee’s studies were such as to qualify him as a Saturnian, a representative of the Renaissance revaluation of melancholy as the temperament of inspiration.

And after the first stage of inspiration, the inspiration coming from immersion in the sciences of number, Agrippa envisages a second stage, a prophetic stage, in which the adept is intent on politico-religious events and prophecies. And finally in the third stage, stage of inspired melancholia, the highest insight into religion and religious changes is revealed. [OP, 86]

First Dee as Saturnian melancholic studies the sciences of number; then he gains prophetic insight into British imperial destiny; and finally vast universal religious visions are revealed to him. [86]

It must be remembered that Dee’s ideas, which we have to try to piece together from scanty and scattered evidence, would have been known to contemporaries through personal contact with this man, who was ubiquitous in Elizabethan society and whose library was the rendezvous of intellectuals.

And there were many works by Dee passing from hand to hand in manuscript which were never published. [86]

Through these lost titles, we catch a glimpse of Dee studying Cabala, immersed in his ‘British History’ researches, and interested in missionary schemes for publishing the Gospel of Christ to the heathen.

second period (1583-9)

In 1583, John Dee left England and was abroad for six years, returning in 1589. During these years on the continent Dee seems to have been engaged in some kind of missionary venture which took him to Cracow, in Poland, and eventually to Prague where the occultist emperor Rudolf II, held his court.

TO this period belong the seances described in Dee’s spiritual diary, with their supposed contacts with the angels Uriel and Gabriel and other spirits. Dee was moving now on the more ‘powerful’ levels of Christian Cabala through which he hoped to encourage powerful religious movements. [87]

Dee’s message appeared to be neither Catholic nor Protestant but an appeal to a vast, undogmatic, reforming movement which drew its spiritual strength from the resources of occult philosophy.

In the context of the late sixteenth century in which movements of this kind abounded, Dee’s mission would not have seemed incredible or strange. Enthusiastic missionaries of his type were moving all over Europe in these last years of the century. One such was Giordano Bruno, who preached a mission of universal Hermetic reform, in which there were some Cabalist elements.

For Dee’s mission, the Monas hieroglyphica is probably the most important clue, for it contained in the compressed form of a magic sign the whole of the occult philosophy.

The first version of it had been dedicated to the Emperor Maximilian II, Rudolph’s father.

In England, Dee had transferred to Queen Elizabeth I the destiny of occult imperial reform, signified by the monas.

‘Both the unmarried Emperor and the Virgin Queen were widely regarded as figures prophetic of significant change in their own day, as symbols of lost equilibrium when they were dead.’ (RJW Evans)

He had sown powerful seeds which were to grow to a strange harvest. It has been shown that the so-called ‘Rosicrucian manifestos’, published in Germany in the early seventeenth century, are heavily influenced by Dee’s philosophy, and that one of them contains a version of the Monas hieroglyphica. The Rosicrucian manifestos call for a universal reformation of the whole wide world through Magia and Cabala. The mythical ‘Christian Red Cross’ (Christian Rosencreuz), the opening of whose magical tomb is a signal for the general reformation, may perhaps, in one of his aspects, be a teutonised memory of John Dee and his Christian Cabala […] [89]

third period (1589-1608)

Returning to England in 1589, Dee found that his supporters in court (Leicester and Sidney) were no longer in a position to back him (disgraced and dead).

Shunned and isolated, Dee was also confronted with a growing witch hunt against him.

Dee’s significance […] is the presentation in the life and work of one man of the phenomenon of the disappearance of the Renaissance in the late sixteenth century in clouds of demonic rumour. What happened in Dee’s lifetime to his ‘Renaissance Neoplatonism’ was happening all over Europe as the Renaissance went down in the darkness of witch hunts. Giordano Bruno in England in the 1580s had helped to inspire the ‘Sidney circle’ and the Elizabethan poetic Renaissance. Giordano Bruno in 1600 was burned at the stake in Rome as a sorcerer. Dee’s fate in England in his third period presents a similar extraordinary contrast with his brilliant first, or ‘Renaissance’ period.

The Hermetic-Cabalist movement failed as a movement of religious reform, and that failure involved the suppression of the Renaissance Neoplatonism which had nourished it. The Renaissance magus turned into Faust. [93]

Being a magus in the most complete sense of the term, John Dee was deeply involved in mathesis, the mystical aspects of number, but his interest in mathematics was practical as well as theoretical. It was Dee’s concern for the advancement of applied science that inspired him to write a treatise on the great benefits to be gained from everyday use of mathematics. To make this part of his philosophy readily available to his less learned contemporaries – those mechanicians who would use mathematics in their trades – Dee wrote his ‘Mathematical Preface to Euclide’ in the vernacular. [160]

Builders, mechanics, navigators, painters, surveyors, and makers of optical glasses were among the mechanicians whose arts, in Dee’s mind, were applied mathematics.

Although mechanicians were not held in especially high esteem by most Elizabethan university graduates, Dee respected practical craftsmen and perceived clearly the role they would play in the advancement of knowledge.

The attitude of Dee and others like him represented a basic change in the scientific outlook, and this change was largely responsible for the tremendous advances in technology that occurred during the Renaissance. It is commonly known that, despite their first-rate scientific minds, the Greeks never fully applied their discoveries.

[why not? Surely Heidegger would say because the world did not disclose itself to them in the way it did to modern man in the modern period – as world picture]

The Greeks lacked the impulse to operate with their cosmos; instead they wished primarily to understand it.

Given this tradition, what was it that inspired Renaissance men like John Dee to apply their scientific philosophy?

The Hermetic texts that influenced Renaissance philosophy so profoundly and emphasised magical operation may also have fostered practical application of scientific knowledge; at least this possibility must be considered. [161]

The desire of the Hermetically inspired Renaissance magus was to control nature, to use it for the benefit of mankind; and, as in Dee’s case, this hope frequently prompted an interest in technology.

Dee: My entent in additions is not to amend Euclides Method, (which nedeth little adding or none at all). But my desire is somwhat to furnish you, toward a more general art Mathematical then Euclides Elementes, (remayning in the termes in which they are written) can sufficiently helpe you unto. And though Euclides Elementes with my Additions, run not in one Methodicall race toward my marke: yet in the meane space my additions either geve light, where thay are annexed to Euclides matter, or geve some ready ayde, and shew the way to dilate your discourses Mathamaticall, or to invent and practise things Mechanically. [Preface to Euclid]

EXPERIMENTATION

Francis Bacon, who is often portrayed as the first English exponent of the experimental method, was by no means original in his call for experimentation […]. Indeed, almost every magician of the sixteenth century advocated some sort of methodological experimentation, and the forms suggested were often more meaningful than Bacon’s.

As FR Johnson pointed out some time ago, John Dee proposed a viable theory of experimental science considerably before Francis Bacon formulated his own.

It is quite possible that Bacon knew of Dee’s treatise in which he terms experimental science ‘Archemastrie’, an art that ‘teacheth to bryng to actuall experience sensible, all worth conclusoions by all Artes Mathematicall purposed, & by true Naturall Philosophie concluded’. Dee continues to explain, ‘Because it procedeth by Experiences, and searcheth forth the causes of Conclusions, by Experiences: and also putteth the Conclusions them selves, in Experience, it is named of some, Scientia Experimentalis‘.

Dee’s entire ‘Mathematical Preface’ is a paean to the fusion of theoretical knowledge with mechanical application. [163]

MANIFESTO

In the Preface, […] Dee manages to outline the entire state of science as it was known in the sixteenth century.

Following an initial discussion of the mystical implications of mathematics, Dee turns to the practical applications of the mathematical sciences, writing:

From henceforth, in this my Preface, I will frame my talk, to Plato his fugitive scholars: or, rather, to such, who well can (and also wil), use their utward senses, to the Glory of God, the benefite of their Countrey, and their owne secret contntation, or honest preferment, on this earthly Scaffold. To them, I will orderly recite, describe & declare a great Number of Artes, from two Mathematicall fountaines [ariithmetic and geometry], derived into the fields of Nature.

The essential point to be remembered about Dee’s preface is that it is a revolutionary manifesto calling for the recognition of mathematics as a key to all knowledge and advocating broad application of mathematical principles. [167]

In his attempt to give the English mechanicians the means to think for themselves about the sciences, Dee advocated testing old beliefs by experiment in the Platonic tradition supported at medieval Oxford, which was more hospitable to science than the predominating Aristotelianism of Renaissance Oxford and Cambridge. This was hardly an approach that the universities would condone, but it did lead to the establishment of scientific method and did encourage the practical application of the mathematical arts. [171]

The centre of English science during the sixteenth century was in London, not at the universities. IN the capital, numerous non-university people, as well as university men like Dee and Rcorde, formed a kind of amorphous third university. Functioning at Syon House, along with Dee’s circle at nearby Mortlake, was the group that gathered around Henry Percy, the ‘Wizard Earl’, during the latter part of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Some of the greatest intellectuals in England were in this circle: Anthony Wood includes Thomas Hariot, John Dee, Walter Warner and Nathaniel Torporly – ‘the Atlantes of the mathematical world’. To these should be added Thomas Allen, a mathematician who in many ways resembled Dee, Christopher Marlowe, John Donne and Walter Ralegh. Ralegh did favours for Dee at court and had considerable respect for the man who directed the exploratory voyages of his half-brothers, Adrian and Humphrey Gilbert. [172]

Besides the Dee and Northumberland circles, the first formal scientific academy in England, Gresham College, was situated in London. The methods of teaching and the orientation towards the quadrivial subjects at the college were in direct contrast to the educational system at Oxford and Cambridge.

It was particularly among extra-university mechanicians and scholars living in the capital, that Dee’s ‘Mathematicall Preface’ enjoyed popularity.

Since it was so commonly known and so highly respected, it is probably almost impossible to estimate its true influence on the development of scientific and philosophical thought in England during the Renaissance. [172]

Dee’s personal role as a teacher and advisor to mechanicians and scientists may have been even more important.

Yet Dee and his treatise have often been neglected by historians of science. A brief history of the dispersion of the preface subsequent to its publication in 1570 will demonstrate its popularity.

When George Gasgoigne decided to publish Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s A Discourse of Discoverie for a new passage to Cataia in 1576, he claimed that one reason for publication was Dee’s approval:

Now let mee say that a great learned man (even M. Dee) doth seeme very well to like of this Discoverie and doth much commende the Authour, the which he declareth in his Mathematical preface to th’english Euclide, I refer thee (Reader) to peruse the same, and thinke it not strange though I be encouraged by so learned a foreleader, to set forth a think which hee so well like of.

In his own century Dee’s preface fully acheived the objectives which he had in mind: it did impress on his compatriots the significance of the mathematical sciences and the benefits to be gained from their study.

As much as Bacon’s Advancement, Dee’s ‘Mathematicall Preface’ is a milestone in the history of English scientific thought.

Dee’s influence on navigation

There was one particular group of mechanicians upon which John Dee and the English Euclide were particularly influential – the navigators.

Dee energetically promoted voyages of exploration, and until 1583 when he left for the Continent with Edward Kelley and the Polish Prince Albertus Alasco, he was perhaps the major guiding spirit behind the glorious saga of English expansion.

[NB. Taylor Tudor Geography]

A current expert on the history of navigation, D W Waters, states flatly that no other single work was so influential in encouraging the development in England of mathematics, navigation and hydrography – in spurring the practical application of mathematics generally – as Dee’s ‘Mathematical Preface’ and the English Euclide. He concludes that Dee’s handling of the mathematical sciences in as a whole is masterful in the preface, but Waters contends that his analysis of navigation and hydrography has never been surpassed.

Dee displayed his eager interest and thorough capability in the geographical sciences from his earliest trips to the Continent. He was in touch with Gemma Frisius, as one time cosmographer to the Emperor Charles V, and another of Dee’s close friends was Pedro Nunez, the Cosmographer Royal of Portugal and Professor of Mathematics at Coimbra.

Dee could also count among his close friends Gerard Mercator, the greatest cosmographer, globe maker and producer of navigational instruments in Europe.

Dee was one of the principal advisers in the early English attempts to find a noerh-eastern passage to Cathay

After searching for a north-eastern passage to Cathay, Englishmen sought a north-western route to the Orient. IN 1576, 77 and 78, Martin Frobisher brought back from his voyage an Eskimo.

Over approximately the same period, Sir Francis Drake was involved in his epic-making voyage around the world, and there is strong evidence to suggest that Dee may have been behind Drake’s voyage. The promotors of Drake’s explorations included Sir Francis Walsingham, the Earl of Leicester, Sir Christopher Hatton, and Sir Edward Dyer, who were all intimate friends of Dee’s [179]

During the 1580s, Dee’s influence in geographical matters was beginning to wane, but he remained the chosen adviser of older men like Sir Humphrey Gilbert. In September 1580, Gilbert entered an agreement, in the presence of witnesses, that granted Dee the rights to all newly discovered land north of the 50th parallel. This would have given Dee the largest part of what is now Canada, but when the voyage was finally undertaken, it failed.

After Gilbert arrived in Newfoundland, his flagship – the Delight – which contained most of his provisions, was wrecked while attempting to reach the American mainland. On the return to England, the ship Squirrel sank and Gilbert was drowned.

The last geographical adventure in which Dee is known to have been directly involved was a plan in 1583 to form a company – with Adrian Gilbert and John Davis (the last seaman Dee ever taught) – to carry out the colonisation, conversion and general exploitation of Atlantis, as Dee termed America. [178]

THE QUEEN’S CONJUROR

measuring

Dee soon discovered, however, that England did not provide the best intellectual viewpoint for surveying the secrets of the universe. To find out all the latest advances, both scientific and astronomical, he needed to travel abroad, in particular to the Low Countries, the place where the light of the Renaissance now shone with its fullest intensity.

On 24 June 1548, Dee arrives at Louvain, near Brussels […]. Dee enrolled on a law course ‘for leisure’, but spent much of his time among the mathematicians, in particular a group clustered around the eminent scientist and physician Gemma Frisius. Frisius (1508-1555) was the university’s professor of medicine and mathematics and practised as a physician in the town. However, his most important work was geographical, not medical.

Frisius pioneered the use of triangulation in land surveying, which enabled the position of a remote landmark to be measured from two points a known distance apart. The method relied on trigonometry, then almost unknown in England.

Under Frisius’s influence, Louvain had become caught up in a rapture of scientific measurement, a mood reflected in the contemporary Flemish picture The Measurers. Frisius set up one of the finest workshops in Europe making measuring instruments. It was run by the engraver and goldsmith Gaspar a Mieica, and some of the leading cartographers of the Renaissance were apprenticed there.

In amongst the cross-staffs and astrolabes in Mirica’s workshop, Dee encountered Frisius’s leading cartographer, Gerard Mercator. He was labouring away on a series of globes and maps that incorporated the discoveries made by Columbus and his successors in the New World. [20]

Dee became fascinated by Mercator’s painstaking work, watching over his shoulder as a picture of the world emerged that to sixteenth-century eyes would have been just as startling and significant as the first photographs of Earth from space were in the twentieth.

Mercator’s maps were starkly geographical, showing a world made up of four continents, its curved surface ‘projected’ onto a rectangular map using a mathematical method that enabled accurate navigation. [20]

It was in the midst of these Measurers of Louvain that Dee’s ‘whole system of philosophising in the foreign manner laid down its first and deepest roots’. He and the thirty-six-year-old Mercator became inseparable. ‘It was in the custom of our mutual friendship and intimacy that, during three whole years, neither of us willingly lacked the other’s presence for as much as three whole days’, he reminisced years later. As a mark of respect and affection, Mercator gave Dee a pair of his globes, one of the earth, the other of the heavens, objects of huge financial and scientific value. In return Dee later dedicated his astrological work, Propaedeumata Aphoristica (1558) to Mercator.

empire (intro)

On 22 November 1577, Dee set off for Windsor Castle, where the court was in residence. In his satchel, he carried the document he had been working on for some time, upon which rested his latest and most ambitious bid to be recognised as the court’s official philosopher and cosmographer.

He arrived at the castle to find a flustered court. It had been an eventful year: […] Sir Francis Drake was preparing for his epic voyage around the globe, which Elizabeth herself was backing with one thousand marks. Within the past few days, a heavenly portend had intensified the histrionic mood. A comet or ‘blazing star’, Dee observed, had ‘bred great fear and doubt in many of the court’. [129]

Dee finally saw the Queen on 25 November […]. They met again on 28 November. Catching the mood of adventure sweeping through the court with Drake’s preparations, Dee laid before the Queen an astounding proposal. England, he said, should challenge Spain’s imperial claim to the New World.

England was at this time a relatively poor nation, on the political as well as geographical margins of the Continent. The court was riddled with debt, its dazzling displays just a facade over the poverty and fragility of everyday life. Militarily, the country was weak […]. So Dee’s proposal to challenge Spain’s imperial might must have seemed ambitious, if not ridiculous.

Following Columbus’s discovery of America in 1492, Pope Alexander VI had issued a bull dividing the New World between Portugal and Spain along an imaginary north-south line which ran three hundred and seventy leagues west of the Azores. This gave Portugal control over the established routes to the West Indies, and Spain possession of any discoveries made in North America and South America west of modern Brazil. The bull had been formalised by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1492, and on this basis the two nations had established their domination not just of America, but of the Atlantic, a position so far barely dented by the English mariners’ ventures.

Dee proposed to the Queen that England should now contest pope Alexander’s division of the globe. He justified this on the basis that several lands declared under the Treaty of Tordesillas to be possessions of the Iberian nations, such as Friesland, had already been colonised by the English. [131]

[Mercator had tipped him off about an incursion by King Arthur into the northern ‘indrawing’ seas around the pole in 530]

Dee had been working on this idea for some time, and suggested featuring it in a series of new works aimed at shifting English foreign policy into a new, adventurous, expansionist mode.

One of these works was planned as his magnum opus, a four-volume survey of the idea of a ‘Brytish Impire’ entitled General and Rare Memorials Pertaining to the Perfect Art of Navigation [see above].

The influence of this extraordinary work is hard to judge, because, despite its subject matter, it has been ignored by most Tudor histories, presumably because Dee’s magical ideas do not fit in with modern conceptions of a scientific basis for discovery.

But it was one of the earliest authoritative statements of the idea of a British Empire, and was delivered to the Queen during the period when Empire was about to make its first appearance on the geopolitical scene.

empire (memorials)

Memorials was a typical Dee production: practical, political, scholarly and mystical.

Its title page combined all these elements in an elaborate allegory that has been called a ‘British hieroglyphic’. Elizabeth sits at the helm of the ship of imperial monarchy, watched over by St Michael, and is drawn by the figure of ‘Lady Occasion’ (‘Lady Opportunity’, in more modern terms) to a fortified citadel overlooking conquered lands. Above Elizabeth hang the Sun, Moon, stars and a glowing sphere bearing the tetragrammaton, a potent Cabalistic formula, all of which shine down their blessings on the enterprise. [132]

The first part of the Memorials focussed on building and financing a substantial navy, the ‘Master Key’ of the whole scheme […].

The second volume was to be a series of navigational tables giving longitudes and latitudes calculated using Dee’s invention, the ‘Paradoxical Compass’ […] Sadly it proved too elaborate to publish, and the manuscript is now lost […].

The contents of the third volume were secret – so secret, Dee pledged, that it ‘should be utterly suppressed or delivered to Vulcan’s custody’. […] Like the second volume, it is now lost.

The fourth volume, Of Famous and Rich Discoveries, has survived […] A badly burned copy is in the British Library, but a list of the contents of the missing parts (the first five chapters) has been summarised by Samuel Purchas.

Dee was also currently writing a manuscript aimed exclusively at the Queen. It was much smaller, but in many respects more potent. Brytanici Imperii Limites (the limits of the British Empire) summarised Dee’s contention that British claims to foreign lands extended well beyond the borders of the British Isles.

News of Dee’s daring proposals spread. Despite the failure of Frobisher’s ore to yield its riches, interest in exploration intensified, and Mortlake quickly became a clearinghouse for the latest information about new discoveries. [134]

Just as the navigators came with news, so privateers gathered in search of opportunities. The two most frequent visitors were Adrian Gilbert and John Davis […]

Adrian was a key figure in an important seafaring dynasty; his brother was Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the man who started the search for the Northwest Passage, and his half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh. The three men set up the ‘Fellowship of New Navigations Atlanticall and Septentionall [i.e. northerly]’, and in 1583 succeeded in getting royal backing to ‘discover and settle the northerly parts of Atlantis, called Novum Orbis’ – in other words, to colonise North America. [134]

The plan was first mooted on 28 August 1580, when Sir Humphrey Gilbert visited Dee. Two weeks later, their discussions culminated with Gilbert’s agreement that, should he succeed in taking possession of the northern parts of the New World, Dee would get the ‘royalties of discoveries all to the north above the parallel of the 50th degree of latitude’ – in other words, most of Canada and all of Alaska.

[…]

Dee’s involvement with these schemes helped define the sense of mission, and of national destiny, that drove the adventurers across the Atlantic.

Elizabeth became increasingly enthusiastic about Dee’s ideas and was anxious to be kept informed of their developments.

[the Queen came to visit Dee in Mortlake, to ask that he come back to court]

He did as he was commanded, two weeks later delivering to her ‘my two rolls of the Queen’s Majesty’s title’, the finished version of his Brytanici Imperii Limites, as she strolled through her gardens at Richmond Palace.

But Cecil, who was by nature conservative, dish, or lay claim to North American lands of doubtful value. Where hotheads such as Robert Dudley and Philip Sidney were seduced by Dee’s vision of a new empire, Cecil was alarmed by it.

From the frontispiece of General and Rare Memorials, through his maps of ‘Atlantis’ and the opportunities described in the Brytanici Imperii Limites, he had summoned a vision of a new world order that might ultimately reunite Christendom, build a new Jerusalem and at the moment Elizabeth hovered on the brink of embracing it, Cecil had wandered in, raised doubts and swept it all away. [137]

[…]

Much he described in the writings he presented to the Queen was to happen in one form or another. The navy would become the ‘master key’ to English military strength; England would challenge the Spanish – as evidenced spectacularly in its 1558 defeat of the Armada; North America would be colonised; a British Empire would emerge, and the expeditions that Dee had in the last few years been helping to plan laid its foundations. But he was to have no part in this future, not even in the adventures of the ‘Fellowship of New Navigations Atlantical and Septentional’. His place in the triumvirate running it was taken by a younger navigator, the man who would soon attempt to found England’s first true colony in the Americas – Sir Walter Raleigh.

conjuring

[…]

The spirit appeared again on 26 March. […] He produced the golden book again and opened it up. He pointed to a series of strange characters, and counted them from left to right, twenty-one in all. ‘Note what they are’, he commanded. Dee copied them down. They were the letters of the celestial alphabet, his first sight of the written language handed down by God to Adam. [192]

After he had finished copying down the characters, Dee asked the spirit about Adrian Gilbert. The previous day, Gilbert had joined them in an action. As they had all gathered in the study, a man had appeared from the direction of Dee’s oratory and laid a ‘fiery ball’ at Gilbert’s feet. Dee wanted to know ‘whether it were any illusion, or the act of a seducer’. ‘No wicked power shall enter this place’, the spirit reassured.

‘Must Adrian Gilbert be made privy to these mysteries?’ Dee anxiously asked. The spirit did not directly answer, and Dee noted in the margin of his notebook that Gilbert ‘may be made privy, but he is not to be a Practicer.’ The spirit then linked Dee and Kelley’s own journey into ‘New Worlds’ with those undertaken by Gilbert and other adventurers. They were all part of the same enterprise. ‘The corners and straights of the earth shall be measured to the depth: and strange shall be the wonders that are creeping in to new worlds. Time shall be altered, with the difference of day and night. All things have grown almost to their fullness,’ the spirit said.

The reference to time would have had a special significance for Dee. For, in the midst of all these actions, and his involvement with the navigators of the New World, he was also working on an important but highly delicate government report on reforming the calendar. [193]

calendar

The previous year, Pope Gregory XIII had issued a bull commanding the Catholic world to remove ten days from October. This had been considered necessary because the calendar introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BC, and adopted by the Christian world at the Council of Nicaea in AD 325, was based on erroneous measurements of solar and lunar cycles. […]

Walsingham had acquired a copy of the Papal bull, and he asked Dee what he thought of it. Dee came up with an alternative plan, which he set out in a sixty-two-page illuminated treatise and delivered to William Cecil on 26 February 1583.

The proposals backed by Pope Gregory, the ‘Gregorian’ calendar, were based on calculations that reached back to the time of the Council of Nicea. Citing a range of authorities including Copernicus, Dee argued that this was the wrong starting date. The Gregorian calendar was ‘singular and insufficient’, as it was based on an artificial foundation, the date of the Council of Nicaea, a political not cosmic coordinate. His doctrinally neutral alternative was a universal (as far as he and all Christians were concerned) moment: the birth of Christ, the true ‘Radix of Time’. However, this necessitated the removal of eleven rather than ten days to realign the calendar.

[…]

Despite the backing of Walsingham and Cecil, the scheme soon foundered.