lost? HOME » PRELUDE: WORLDMAKING » DEVELOPING A WORLD PICTURE

PREPARATORY FOR PHILOSOPHY OF THE MACROCOSM (INTRODUCTION OF THEMES OF TECHNICS + EMPIRE, LAND + SEA, &C., &C.) • ESTABLISHMENT OF TIMEFRAME (MODERN PERIOD: DEE/FLUDD → THE SUNSET)

DEVELOPING A WORLD PICTURE

THE FUNDAMENTAL EVENT OF THE MODERN AGE IS THE CONQUEST OF THE WORLD AS PICTURE

TECHNICAL HISTORY OF THE MACROCOSM

The diagram comes from the title page of Robert Fludd’s Technical History of the Macrocosm, the second part of the Tomus Primus of his great work, Utriusque Cosmi… Historia (his History of Two Worlds). Frances Yates will help us to situate it:

The volume on the technical history of the Macrocosm forms part of the long series of the Utriusque Cosmi Historia which was published at Oppenheim, in Germany, by the firm of John Theodore De Bry. Since this series is rather confusing, I set out its parts here in simplified form.

Tomus Primus. On the Macrocosm

In two parts. Part I on the metaphysics of the Macrocosm was published in 1617, with a dedication to James I. Part II is on ‘the technical history of the Macrocosm’ […]. It was published in 1618.

Tomus Secundus. On the Microcosm

In two parts, namely on the metaphysics of the Microcosm and on ‘the technical history of the Microcosm, which correpsonds to the two parts of the Macrocosmos Tomus. They were, however not published seperatley, like the Macrocosm parts, but in one volume, in 1619. The ‘technical history of the Microcosm’ contains the ‘Ars memoriae’ […] [Frances Yates, Theatre of the World, p.44]

This second volume was not the last in the publication series, but in order to keep things as simple as possible, Yates leaves the subsequent work aside to focus on the two parts of the two Tomus, which she referst to as Macrocosm I & II and Microcosm I & II. The part that is of interest here, therfore, is Macrocosm II in Yates’s shorthand.

The subjects of Macrocsom II, ‘the technical history of the Macrocosm’ are set out on its title-page in the form of images on a wheel. These images, and their order, constitute a mnemotechnic for remembering the subjects of which the book will treat. [TW, 44]

We are going to take an interest in these subjects, and also in the broader context of Fludd’s work on metaphysics and technics. At a certain point we are going to diverge a little from Yates’s arguments, following a Heideggarian inflection, to take things in a different direction. But, let’s stay with her for the time being, grateful for the huge contribution she has made to opening these works for modern readers.

Yates is going to argue that the diagram proves Fludd’s interest by way of John Dee in the work of Vitruvius, and this is very significant for the broader theme of her book where she seeks to articulate a previously unacknowledged current of thought, working behind the scenes, as it were, in the development of Elizabethan/Jacobean theatre.

Before we begin to study the subjects of ‘the technical history of the Macrocosm’, let us gaze attentively at this helpful mnemonic title-page. The full Latin title may be translated as ‘On the Ape of Nature or the Technical History of the Macrocosm divided into Eleven Parts’. Art as the Ape of Nature sits in the centre of a wheel divided into eleven sections containing images representing the eleven parts into which the volume is divided. He points with a wand to a book containing numbers. All nature is based on number and the Ape of Nature, man, must therefore base all his arts on number. This refers to section 1 of the volume, on arithmetic, algebra, geometry, with subsections on the relation of number to military art, music, astronomy, astrology, and geomancy. To keep to the order in which the subjects are treated in the volume, we must now move to the man playing the organ, representing music, which is the subject of section 2. Next we look at a man surveying with a cross staff, with quadrant and compass beside him, who represents section 3, on land measurement. The man looking at a house stands for section 4, on optics. The painter brings us to section 5, on painting proportion and perspective. The segment of a fort, bombarded with guns, represents section 6, on military art. The instrument for lifting weights, of a type used by builders, brings us to section 7, on motion, which includes machines and mechanical devices of many kinds. The clock and the dial stand for section 8, on time-measurement. The globe refers to section 9, on cosmography and geography. The astrologer represents section 10 on astrology. Finally, the shield with the dots on it stands for geomancy, which is treated in the last, or eleventh, part of the volume. [TW, 45]

For clarity, the eleven sections in the order they appear in the wheel are:

1. Number

2. Geodesy

3. Optics

4. Perspectival representation

5. Military arts

6. Motion and mechanics

7. Horology

8. Cosmography and geography

9. Astrology

10. Geomancy

11. Music

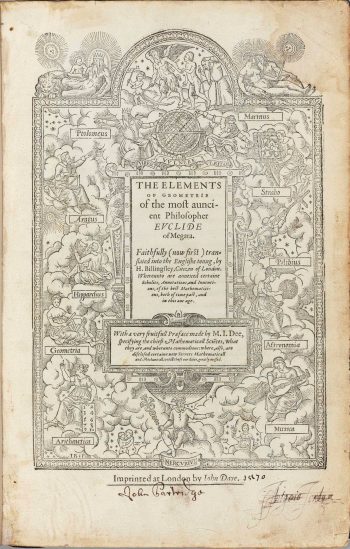

What Yates finds interesting in the context of her argument for a Vitruvian influence is that, with the exception of Geomacy, these are all the subjects that Vitruvius subordinates to Architecture (which Fludd does not mention). Yates is not so much arguing for a direct influence (although she is sure Fludd knew Vitruvius’s text). Instead, she wants to underline that Fludd is responding to John Dee’s 1570 preface to Euclid, which itself is structured on Vitruvius’s work.

For Yates, Dee was a conduit, transfusing continental renaissance architectural theory into the very heart of Elizabethan England. Failure to see this is a ‘striking illustration of the extraordinary neglect by modern scholars of the work of John Dee’. The whole preface, says Yates, is actually based on Vitruvius, and ‘the mathematical subjects that Dee wishes to encourage are those which Vitruvius states that an architect should know.

The Preface opens with general Pythagoro-Platonic mystical discussion of number. Then he enumerates the sciences dealing with number, which are arithmetic, algebra, geometry, and goes through other sciences showing their dependence on number. Military art uses number in the science of tactics; law uses it in its study of just distribution. Geometry is essential to the ‘mechanician’ in his sciences of measuring. Here Dee lists as among the geometrical arts, geodesy, or surveying, geography, or the study of the earth, hydrology, or the study of the oceans. ‘Stratarithmetrie’ which is again military art or the disposal of armies in geometrical figures. Next he comes to perspective, a science in which he was particularly interested; then to astronomy, then to music. Astrology is also an ‘art mathematical’ and one which particularly shows forth the glory of God who made the heavens in his wisdom. […] [TW, 22]

In Macrocosm II, Yates argues, Fludd ‘enormously expands Dee’s treatment of the subjects’, illustrating them with many engravings. Yates even says that some of Fludd’s expansions may well be Dee’s own work, undertaken in unpublished manuscripts that Fludd is here disseminating without acknowledgement.

With a warning to the reader that the study of Macrocosm II as derivative of Dee is an ‘intricate matter’, and that the attempt will be incomplete and selective, Yates enters into the detail of her argument. The Dee provenance is interesting to us, so we will make a few of our own selections from Yates’s work.

The Ape of Nature points to the book containing numbers as the basis of all the arts. Vitruvius had said that the architect must be versed in mathematics, but Fludd’s extremely long treatment of arithmetic, algebra, geometry in their relation to other arts corresponds to the opening of Dee’s Preface on arithmetic, algebra, geometry and their connections.

[…]

[…] we turn our attention to the man engaged in surveying a town. Vitruvius had said that the architect must understand land measurement; Dee had a paragraph on geodesy; Fludd expands surveying into a very long and very fully illustrated section of his book.

The art of surveying had been greatly developed by Dee’s able associates and disciples in the flourishing London school of applied mathematics. Leonard Digges wrote a treatise on it, called Pantometria, which his son Thomas Digges, who was Dee’s close disciple, published with additions in 1571, the year after the publication of Dee’s Preface. This treatise is illustrated with cuts showing men surveying with cross staff and quadrant […]. Fludd certainly had this book by him when composing his section 3, on surveying […].

[…]

In the next two sections on optics and on painting (represented on the mnemonic wheel by a man looking at a house and the painter) Fludd again appears in the light of an instructor, of someone who is setting out to teach perspective drawing and the elements of proportion in figure drawing […].

Vitruvius had said that the architect must know optics; Dee had mentioned optics and perspective in the Preface. Fludd as usual greatly expands and heavily illustrates these themes.

[…]

Fortification and military art are, of course, Vitruvian subjects and they were touched on by Dee in the Preface. Fludd’s section on these subjects is one of the most impressive and lavishly illustrated in the book. […] Fludd on military art represents Vitruvius brought up to date; the forts which he illustrates so profusely are modern, Renaissance angle-bastions, designed to resist gunfire, and the weapons include guns.

The aspects of the proficiency of Dee and his disciples in the mathematical arts in which Elizabethan government had taken most interest had been those connected with the development of navigation and with improved methods of defence in warfare, of great importance in view of the threat of Spanish invasion which loomed over the country. Gunnery was one of Dee’s specialties […].

Fortification is, of course, a branch of architecture, and Fludd is at pains to prove that it is a mathematical art by demonstrating the geometrical basis of fortification plans. Yet he is also providing a kind of pattern book of fortification […].

Next after fortification on the mnemonic wheel we see a machine for lifting weights. […] The appearance of this builder’s machine as typifying the section on motion, with its wealth of illustrations of machines and mechanical devices of many kinds worked by pulleys, levers, screws, and so on, is an instance of close dependence on Vitruvius by Fludd, for Vitruvius’s tenth book on motion is about such machinery. […]

As usual, Fludd is concerned both to show that all these mechanisms are mathematical arts dependent on number, and also to expand the subject with many illustrations thereby providing a kind of illustrated textbook on mechanics which will be of practical use to those interested in this mathematical art (just as his treatises on surveying, perspective, painting, are intended to be of use to practitioners of those mathematical arts). […]

In the concluding pages of Fludd’s section ‘on motion’ we are in the realms of what Dee would have called ‘Thaumaturgike’, though Fludd does not use Dee’s term for the various branches of the mechanical arts. […]

[…]

I shall not attempt to discuss the next three items shown on the memory wheel illustrating the subjects of the ‘technical history of the Macrocosm’. These are time measurement with clocks and dials […]; cosmography and astronomy, represented by the two globes in the next compartment of the wheel; followed in the next section by the horoscope diagram representing astrology. These were all Vitruvian subjects, all discussed by Dee in the Preface, and are all expanded at very great length by Fludd as mathematical arts for which he provides practical guidance.

With the next subject on the memory plan, geomancy, represented by the dots on the shield, we reach a subject which is not in Vitruvius, nor mentioned by Dee. Its presence among the Vitruvian subjects introduces a strongly magical tinge into Fludd’s survey of these subjects. […]

Pausing here for a moment’s reflection let us try to sum up what we have learned from the preceding analysis (which has omitted so much) of Fludd’s ‘technical history of the Macrocosm’. In following its subjects, we have been within hail of vast Renaissance themes, we have been passing easily, like Leonardo da Vinci, from art to science, from proportion to machines, and we have seen that what holds all these subjects together is Vitruvius – Vitruvius as interpreted by Dee as the storehouse of all workmanship and the fount of mathematical arts. It it through number, as the Ape of Nature shows us with his wand, that all these subjects are basically one, held together by number […].

But for Vitruvius, all these subjects subserved architecture, which was the subject of his book.

[TW, pp. 45-54]

This presents something of a problem, to which Yates’s answer is in effect that Fludd integrated it into the Vitruvian subject of Music, which was she says the most important of all for Fludd. Through this integration, he elevates music to the position occupied by architecture in Vitruvius. Why would he do this?

Dee had known that the basic theory of proportion in Macrocosm and Microcosm came from Vitruvius and had directed his readers to ‘looke in Vitruvius’ and find it there. Fludd was certainly familiar with both Vitruvius and Dee’s Preface and, moreover […], his whole musical philosophy of Macrocosm and Microcosm, his whole History of these Two Worlds, is imbued with the Macrocosm-Microcosm analogy expressed in terms of musical production.

Fludd writes of music in Macrocosm II: ‘Amidst all these delights is the divine gift of Apollo who receives the adoration of all; whence arise on all sides peace and concord through the mysteries of harmony and symphony in which the concords of the heavens and the elements are linked together. The whole universe must perish and be reduced to nothing in warring discord should these consonances fail or be corrupted‘.

Music is the principle of harmony and concord linking the heavens with the elements, it is a central principle of his neo-Platonic magical system, and so it is lifted to the apogee of his systematic catalogue of technics. Although this is certainly important, and called for some explanation, it is in fact of relatively little interest in the context of our own reading of the diagram.

In her stock-taking above, Yates made two points which are worth highlighting. Firstly, that Fludd is working in the intellectual context of ‘vast Renaissance themes’. Central to this, although not explicitly stated here, would be the humanism integral to the macrocosm/microcosm of the Two Worlds. The other is that all of the arts come back to one same source from which they emanate – the science of measure, illustrated by a book of numbers: mathematics.

We are going to return to Fludd, the technical history of the Macrocosm, to Dee and his position in Elizabethan/Jacobean England, to the world that was beginning to figure on their horizon. But now, having taken a first look at Fludd’s wheel, we will turn to a text written some 320 years later which in its own way will refer back to just the context we have been exploring: Martin Heidegger’s ‘The Age of the World Picture’.

THE AGE OF THE WORLD PICTURE

TIME-LAPSE

‘The Age of the World Picture’ [PDF] is included in the collection of writings published in translation as The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays [QCT], where it is one of two essays making up Part III (the other being ‘Science and Reflection’). Although it follows after ‘The Question Concerning Technology’, the first essay in Part I of the English collection (the other in this part being ‘The Turning’), it predates it in initial conception by more than a decade.

‘The Question Concerning Technology’ and ‘The Turning’ developed out of lectures first given in 1949/50, which, after being revisited and expanded in the mid-1950s, were eventually published in 1962. ‘The Age of the World Picture’, which was first published in a collection titled Holzwege in 1952, was in fact delivered as a lecture in Freiburg im Breisgau under the title ‘The Establishing by Metaphysics of the Modern World Picture’ in 1938. Along with the other essays in Holzwege this essay was repeatedly revised and clarified in the nearly fifteen years between its first public outing and publication.

In 1938, the year of the lecture on the World Picture, Heidegger was in the middle of his initial deep exploration of the work of Nietzsche, undertaken in a series of four lecture courses at the University of Freiburg (the courses ran from 1936-40 and would eventually be published, along with other material, in two large volumes in 1961, coming to the English reader in four volumes between 1979-84 – my own notes on some of this material can be found here), and ‘The Word of Nietzsche: ‘God is Dead”, the long essay making up the central Part II of QCT, delivered repeatedly in 1943, draws extensively on content from the lectures.

In this rather complicated chronology it is important to realise that the essays as they have eventually come together in QCT are in no way sequential. By 1952, when ‘The Age of the World Picture’ (AWP) was stabilised in its current form, Heidegger had completed his deep dive of Nietzsche’s works and was already in the process of drafting and redrafting the two essays from Part I. So although AWP would seem to be the earlier work, being originally composed in 1938, the pacing of the publication process and Heidegger’s working method mean that in a sense it also follows on from the more explicit work on the essence of technology, and on Nietzsche as the last metaphysician. The works therefore counter-sign and ground each other, and this is how they will be taken.

[Additional notes made from these essays can be found here]

THE ESSENCE OF MODERN TECHNOLOGY (EXPOSURE)

‘Machine technology remains up to now the most visible outgrowth of the essence of modern technology, which is identical with the essence of modern metaphysics‘ [AWP, 116].

There could be no more lucid statement on Heidegger’s understanding of the essence of modern technology than the above quotation from ‘The Age of the World Picture’. We draw two crucial lessons: 1. the essence of technology is ‘by no means anything technological’ (as Heidegger famously put it in QCT) – so in the same way that the essence of a tree is not to be confused with any particular tree, the essence of technology is not to be found in any particular technology. Machine technology is just a visible outgrowth from the essence of technology,and 2; the essence of modern technology is in fact identical with the essence of modern metaphysics.

Heidegger liked to locate fundamental statements within the work of philosophers or poets he was reading which he would use as a kind of fixed reference point, a landmark that would help him to make sense of the rest of the territory. If we were looking for something similar in his work, the second part of the opening quotation, identifying the essence of modern technology and modern metaphysics would be a promising candidate, especially with respect to the development of his thought after Being and Time.

In QCT, Heidegger first seeks to establish technology, in its essence, ‘as a mode of revealing’, which is to say it determines the way in which the world is encountered. The kind of revealing that takes place in the context of modern technology, that frames (to anticipate a little) our encounter with the world, is one in which the world shows itself as a resource. ‘The earth now reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit’. The world is there for man as what Heidegger calls the ‘standing-reserve’ [Bestand].

The word expresses here something more, and something more essential, than mere ‘stock’. The name ‘standing-reserve’ assumes the rank of an inclusive rubric. It designates nothing less than the way in which everything presences that is wrought upon by the challenging revealing. [QCT, 17]

Crucially, however, man has little control over the way in which the world reveals itself for him.

Since man drives technology forward, he takes part in ordering as a way of revealing. But the unconcealment itself, within which ordering unfolds, is never a human handiwork […]. Wherever man opens his eyes and ears, unlocks his heart, and gives himself over to meditating and striving, shaping and working, entreating and thanking, he finds himself everywhere already brought into the unconcealed. The unconcealment of the unconcealed has already come to pass whenever it calls man forth into the modes of revealing allotted to him. [QCT, 19]

Technology as a mode of revealing is predetermined by the mode of unconcealment of what is, with which it shares an essence. Heidegger at this point introduces the word Ge-stell [Enframing], to designate the way that man is in a sense programmed to encounter the world.

Enframing means the gathering together of that setting-upon which sets man upon, i.e. challenges him forth, to reveal the real, in the mode of ordering, as standing-reserve. [QCT, 20]

In Enframing, that unconcealment comes to pass in conformity with which the work of modern technology reveals the real as standing-reserve. [QCT, 21]

For Heidegger, there is a significant danger associated with Enframing as mode of encountering the world:

As soon as what is unconcealed no longer concerns man even as object, but does so, rather, exclusively as standing-reserve, and man in the midst of objectlessness is nothing but the orderer of the standing-reserve, then he comes to the point where he himself will have to be taken as standing-reserve. [QCT, 27].

At its extreme point, Enframing, therefore, presents an extreme danger – man himself becomes nothing but a resource just like the rest of the world when it is encountered as standing-reserve. It is here that Heidegger turns to a couplet by Hölderlin to argue that it is at this extremity that the possibility of salvation, of the ‘saving power’, will begin to make itself known. Through a kind of lighting up, an in-flashing, we read in ‘The Turning’, another possibility announces itself.

But we are a long way ahead of ourselves.

We were discussing Heidegger’s identification of the essence of modern technology with the essence of modern metaphysics. We have looked a little at how the essence of technology, which is not to be located in any technological expression, is actually coordinate with a particular way in which the world reveals itself to man. We might speak here of the exposure of the world, which is set forth, made visible, and made available through Enframing. We can begin to see why Heidegger links the fates of metaphysics and technology in this way, but what is not clear yet, and what will be important as we make our way back to Fludd and Dee, is the meaning of the word ‘modern’ in the opening citation.

THE MEANING OF THE MODERN

At what point does man become modern? A couple of quotations by way of initial orientation:

Chronologically speaking, modern physical science begins in the seventeenth century. In contrast, machine power technology develops only in the second half of the eighteenth century. But modern technology, which for chronological reckoning is the later, is, from the point of view of the essence holding sway within it, the historically earlier. [QCT, 22]

The whole of modern metaphysics taken together, Nietzsche included, maintains itself within the interpretation of what it is to be and of truth that was prepared by Descartes. [AWP, 127]

Given the identification of the essence of modern technology and modern metaphysics, we should not be surprised to find their initial expressions coordinated in the 17th Century. Before going any further, it is important to reiterate Heidegger’s point above that man is not in control of the way in which the world reveals itself to him. So when a proper name like Descartes identifies a metaphysical position, we should not take that to mean that Heidegger thinks that Descartes is responsible for the mode of revealing he exposes in his work (unless we take that to mean that he responds to that mode of revealing). His work is an expression: without wishing to confuse things too much, since this usage is a displacement from Fludd, a figure like Descartes can be seen as a microcosmic expression of the macrocosm, where the macrocosm is the mode of revealing in which man stands in his encounter with the world. An essential thinker like Descartes articulates this mode, reflecting the macrocosm in his work. Similarly, if, at the culmination of the modern period, a figure like Mallarmé is able to read from nature, with the ‘lucid eye of the poet’, a catastrophe which he will figure as a sunset, this is because his work stands in microcosmic relation to events taking place in the macrocosm.

But we have strayed towards the end again, when we were trying to understand something about the beginning.

In the first quotation above, Heidegger gives an initial chronology: first comes physical science in the Seventeenth Century, and then, in the second half of the Eighteenth, comes machine power technology (the modern technology Heidegger is discussing). However, this cannot be the end of the story because the modern physical science that seems to subtend technology would not have been possible were it not for a particular mode of revealing which Heidegger calls technological – provided it is thought essentially, when it is quite literally confused with modern metaphysics. This mode of revealing comes before physical science, in a deeper chronology, as its condition of possibility. Heidegger asks:

But after all, mathematical physics arose almost two centuries before technology. How, then, could it have already been set upon by modern technology and placed in its service? Surely technology got underway only when it could be supported by exact physical science. Reckoned chronologically, this is correct. Thought historically, it does not hit upon the truth. [QCT, 22]

There is a distinction between the chronological and the historical in Heidegger’s thinking. In the merely chronological, what is essential does not appear as such:

For already in physics the challenging gathering-together into ordering revealing holds sway. But in it that gathering does not yet come expressly to appearance.

[…]

All coming to presence, not only modern technology, keeps itself everywhere concealed to the last. Nevertheless, it remains, with respect to its holding sway, that which precedes all: the earliest. [QCT, 22]

By way of recap: modern technology and modern metaphysics are essentially identical for Heidegger; they are both essentially a particular mode of revealing of the world, through which it comes to presence for man as a resource; this period begins before the emergence of modern technology as such, when its essential nature is at first concealed, but it makes possible physical science which in turn engenders the technologies of the modern world.

We know, then, that the modern world is only possible on the basis of a particular exposure, mode of revealing, or perhaps, we should say, disclosure.

THE WORLD PICTURE

At the very beginning of ‘The Age of the World Picture’, Heidegger writes:

Metaphysics grounds an age, in that through a specific interpretation of what is and through a specific comprehension of truth it gives to that age the basis upon which it is essentially formed. This basis holds complete dominion over all the phenomena that distinguish the age. [AWP, 115]

Heidegger is trying to interrogate this essential ground, which in his deep chronology precedes physical science, which in turn engenders modern technologies. At the start of AWP, Heidegger lists five phenomena which he says are essential to the modern age: science; machine technology; art becoming aesthetics; human activity conceived as culture; the loss of the gods. And he asks: ‘what understanding of what is, what interpretation of truth, lies at the foundation of these phenomena?’. The essay will limit itself to examining just one phenomenon, which we have already seen is crucial to the emergence of modern technologies, but is itself grounded on a more original disclosure of the world: science.

It is a matter of finding ‘what understanding of what is and of truth provides the basis for the essence of science’.

If we succeed in reaching the metaphysical ground that provides the foundation for science as a modern phenomenon, then the entire essence of the modern age will have to let itself be apprehended from out of that ground. [AWP, 117]

The essence of science, says Heidegger, is research. But what is the essence of research? This is to be found in the way it establishes itself as a ‘procedure within the realm of what is’. But, again, this begs the question: what is a procedure? a procedure is not just a method or methodology, but requires an ‘open sphere’ within which it can operate. So, the crucial thing, the ‘fundamental event’ in research, is the opening of this sphere. This opening is achieved by the projection of a ground plan, which sketches out in advance how the procedure will advance in the given sphere.

It is in this way that the procedure is able to secure for itself a particular sphere of objects within the realm of being. In order to advance, research projects forward in such a way that it will be able to proceed into a given realm of being.

As an example, Heidegger takes the earliest, and what he calls the ‘normative’ science of mathematical physics (so not just any example).

Ta mathēmata, says Heidegger, meant for the Greeks precisely ‘that which man knows in advance in his observation of whatever is and in his intercourse with things’. If we encounter three apples on a table, we see that there are three of them. The number, three, is something we already know, and that is why it is mathematical. Numbers are not the essence of mathematics – they are just a striking example of the ‘always-already-knowns’, and therefore a familiar example of the mathematical.

If physics takes shape explicitly, then, as something mathematical, this means that, in an especially pronounced way, through it and for it something is stipulated in advance as what is already known.

That stipulating has to do with nothing less than the plan or projection of that which must henceforth, for the knowing of nature that is sought after, be nature: the self-contained system of motions of units of mass related spatiotemporally. [AWP, 119]

Every event, says Heidegger, must fit with this groundplan. And ‘only within the perspective of this groundplan does an event in nature become visible as such an event.’ All these events must be ‘defined’ in advance as spatiotemporal magnitudes of motion, and ‘such defining is accomplished through measuring, with the help of number and calculation’.

If physics is mathematical, it is because it operates by way of mathematical precognition. Being calculated in advance, Nature becomes ‘set in place’. Only that which becomes an object in this way, says Heidegger, ‘is – is considered to be in being’.

This objectifying of whatever is, is accomplished in a setting-before, a representing, that aims at bringing each particular being before it in such a way that man who calculates can be sure, and that means certain, of that being. [AWP, 127]

And then comes the crucial sentence: ‘We first arrive at science as research when and only when truth has been transformed into the certainty of representation’. This expression of truth is very precisely located: ‘What is to be is for the first time defined as the objectiveness of representing, and truth is first defined as the certainty of representing, in the metaphysics of Descartes’.

It is at this point that man for the first time becomes subject: subiectum translates the Greek hypokeimenon and means that-which-stands-before. At first, for the Greeks, says Heidegger, this metaphysical meaning of the concept of subject has no special relationship to man, and none to the I. In the modern age, and most explicitly in the work of Descartes, man becomes the primary and only real subiectum – he becomes the relational centre of that which is as such.

It is here that Heidegger introduces the concept of the Weltbild or World Picture.

When we reflect on the modern age, we are questioning concerning the modern world picture. We characterise the latter by throwing it into relief over against the medieval and the ancient world pictures. […] Does every period of history have its world picture […]?

This is significant for Heidegger. Is it the case that other ages have even had a world picture that they could have recognised as such? ‘Or is this, after all, only a modern kind of representing, this asking concerning a world picture?’

What is a world picture? Firstly, what is the ‘world’ and, what is the ‘picture’ in this expression?

The ‘world’ here is simply everything that is, in its entirety. Not just nature, but history as well, and the ground of the world.

The ‘picture’ in world picture is more than just an image or imitation. Heidegger says it is like the picture in the idiom ‘to get the picture’ – ‘the matter stands before us’. To get the picture with respect to something ‘means to set whatever is, itself, in place before oneself just in the way that it stands with it. There is, however, a determination missing here: what stands before us stands before us in the world picture as a system.

Hence world picture, when understood essentially, does not mean a picture of the world but the world conceived as picture. What is, in its entirety, is now taken in such a way that it first is in being and only is in being to the extent that it is set up by man, who represents and sets forth. Wherever we have the world picture, an essential decision takes place regarding what is, in its entirety. [AWP, 130]

In answer to his question, for Heidegger it is impossible to conceive of another age having a world picture in this sense. To have a world picture already implies having a particular world picture. If not, no world picture.

What is decisive is that man himself expressly takes up this position as one constituted by himself […] and that he makes it secure as the solid footing for a possible development of humanity […]. There begins that way of being human which mans the realm of human capability as a domain given over to measuring and executing, for the purposes of gaining mastery over that which is as a whole. [AWP, 132]

DEE + THE ENGLISH RENAISSANCE

DEE’S MANIFESTO: PREFACE TO EUCLID

nb. additional notes on dee and the english renaissance can be found here

My entent in additions is not to amend Euclides Method, (which nedeth little adding or none at all). But my desire is somwhat to furnish you, toward a more general art Mathematical then Euclides Elementes, (remayning in the termes in which they are written) can sufficiently helpe you unto. And though Euclides Elementes with my Additions, run not in one Methodicall race toward my marke: yet in the meane space my additions either geve light, where thay are annexed to Euclides matter, or geve some ready ayde, and shew the way to dilate your discourses Mathamaticall, or to invent and practise things Mechanically.

Above we saw with Frances Yates the degree to which Robert Fludd’s diagram from the title page of The Technical History of the Macrocosm was rooted in Dee’s Preface. Whatever extrapolations are made from Fludd, it is important to realise that his interest in Dee was in no way idiosyncratic. Dee’s preface was an intellectual event in Renaissance England.

Dee, we know, was integrated into Elizabethan England through a complex network of connections. His home in Mortlake housed one of the great Libraries of the day, and was frequented by disciples and peers; he was well known at court, and amongst the adventurers, the Gilberts, Raleighs, Drakes of this world, who we will see, drew on his navigational expertise; and he maintained intellectual connections with a network spread throughout Europe. He was something of a cult figure, probably the model for Prospero, and along with the handful of published works, many of his texts circulated widely as manuscripts. Yates refers to the Dee ‘movement’, and she, like Peter French in his biography, speaks of the Preface as the manifesto of this movement.

The essential point to be remembered about Dee’s preface is that it is a revolutionary manifesto calling for the recognition of mathematics as a key to all knowledge and advocating broad application of mathematical principles. [French, 167]

In the first instance, we note two important and interrelated points: 1. the Preface, like all of Dee’s essential writings, was written in the vernacular; and 2. it was at pains to emphasise the practical applications of mathematics.

The translation project itself, and Dee’s Preface, repositioned mathematics away from the academy towards a much more practical application. He states his intention clearly in the extract above: he does not want to amend Euclid, but to emphasise, without straying from the text of the Elements, a more general art – to elucidate the text where necessary, and, crucially, to show how mathematical discourse can be broadened so that it can serve to help in the ‘practise of things mechanically’.

After an initial discussion of mathematical concepts, the Preface, therefore, changes tack:

From henceforth, in this my Preface, will I frame my talke, to Plato his fugitiue Scholers: or, rather, to such, who well can, (and also wil,) vse their vtward senses, to the glory of God, the benefite of their Countrey, and their owne secret contentation, or honest preferment, on this earthly Scaffold. To them, I will orderly recite, describe & declare a great Number of Artes, from our two Mathematicall fountaines, deriued into the fieldes of Nature.

From the two mathematical fountains (arithmetic and geometry), Dee will now describe a number of Artes which are to be enhanced. Knowledge of Geometry will be of value in the various land measurements or Geodesies: Geographie, Chorographie, Hydrographie and Stratarithmetrie. But also, other sciences – Perspectiue, Astronomie, Musike, Cosmographie, Astrologie, Statike, Anthropographie, Trochilike, Helicosophie, Pneumatithmie, Menadrie, Hypogeiodie, Hydragogie, Horometrie, Zographie, Architecture, Nauigation, Thaumaturgike and Archemastrie – will be served by mathematics.

This shift in the discourse is a massive displacement. If we are attentive, we can feel the centre of gravity move. Dee was deeply immersed in the intellectual and political currents of his time, and here, in his manifesto, it is as though he discerned something fundamental. Let’s say essential.

EMPIRE

Strange to say – and everything about Dee is strange – the megalomaniac proved prophetically right: perhaps he was not a clairvoyant for nothing after all

◊

The Arte of Nauigation, demonstrateth how, by the shortest good way, by the aptest Directiõ, & in the shortest time, a sufficient Ship, betwene any two places (in passage Nauigable,) assigned: may be cõducted: and in all stormes, & naturall disturbances chauncyng, how, to vse the best possible meanes, whereby to recouer the place first assigned. What nede, the Master Pilote, hath of other Artes, here before recited, it is easie to know: as, of Hydrographie, Astronomie, Astrologie, and Horometrie. Presupposing continually, the common Base, and foundacion of all: namely Arithmetike and Geometrie. So that, he be hable to vnderstand, and Iudge his own necessary Instrumentes, and furniture Necessary: Whether they be perfectly made or no: and also can, (if nede be) make them, hym selfe. As Quadrantes, The Astronomers Ryng, The Astronomers staffe, The Astrolabe vniuersall. An Hydrographicall Globe. Charts Hydrographicall, true, (not with parallell Meridians). The Common Sea Compas: The Compas of variacion: The Proportionall, and Paradoxall Compasses Anno. 1559. (of me Inuented, for our two Moscouy Master Pilotes, at the request of the Company) Clockes with spryng: houre, halfe houre, and three houre Sandglasses: & sundry other Instrumẽtes: And also, be hable, on Globe, or Playne to describe the Paradoxall Compasse: and duely to vse the same, to all maner of purposes, whereto it was inuented. And also, be hable to Calculate the Planetes places for all tymes. [from the preface]

Number fetishist, practical scientist, and politiker, Dee was also the great prophet of the British Empire.

When Elizabeth came to the throne in 1558, and hardly a soul had awoken to the dream of Empire, John Dee became her astrological and scientific adviser, exerting his greatest influence at court as Elizabethan identity was being forged. He was the technical and ideological driving force behind the voyages of discovery that were planned and fomented during that period, and essential to a developing understanding of what they might mean. In the 1570 Preface, Dee gives a sense of his deep understanding of the technical nous required for this kind of enterprise.

Comparable with the way in which the Vitruvian subjects come together in the service of Architecture, the great vortex in Dee’s Preface seems to be navigation. At least for the Englishman:

Yet, this one thyng may I, (iustly) say. In Nauigation, none ought to haue greater care, to be skillfull, then our English Pylotes. And perchaunce, Some, would more attempt: And other Some, more willingly would be aydyng, it they wist certainely, What Priuiledge, God had endued this Iland with, by reason of Situation, most commodious for Nauigation, to Places most Famous & Riche.

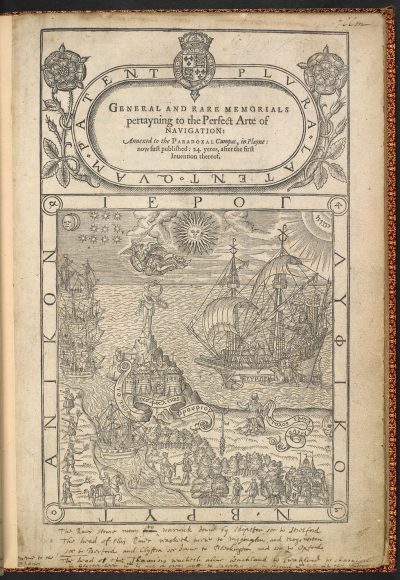

The last words in this sentence echo the title of the projected final part of his incomplete opus, General and Rare Memorials, ‘Famous and Rich Discoveries’. During the 1570s, Dee had continued to involve himself in the technical and moral imperatives of English expansion through discovery and land appropriation, with everything coming to something of a head in the years around 1577 with the publicaiton of the first part of General and Rare Memorials, [The General and Rare Memorials was planned as a tetralogy. Its constituent volumes seem to have been composed sequentially, beginning with The Brytish Monarchie, which was drafted in the first six days of August 1576, and ending with Famous and Rich Discoueries, which Dee started writing before 24 March 1577 and finished on or after 8 June 1577. The first volume, the only one to published, went the printer on the 19th August 1977 – ref], the redaction of the Brytanici Imperii Limites (The Limits of the British Empire, commonly referred to as the Limites), and his practical involvement in Frobisher’s, Gilbert’s, and probably Drake’s voyages.

In the first published part of General and Rare Materials, titled The British Monarchie, Dee advocates the building of a powerful navy. French writes:

Dee’s title page elucidates his overall scheme. The inscription in Greek that surrounds the picture explains that the whole is a British hieroglyph and that a more complete explanation of the picture’s symbolism is to be found in the text itself. The reference is to the following passage:

Why should we not HOPE, that, RES-PUBL. BRYTANICA, on her knees, very Humbly, and ernestly Soliciting the most Excellent Royal Majesty, of our ELIZABETH, (Sitting at the HELM of this Imperiall Monarchy: or, rather, at the Helm of the IMPERIALL SHIP, of the most parte of Christendome: if so, it be her Graces Pleasure) shal obteyn, (or Perfect Policie, may perswade her Highnes,) that, which is the Pyth, or intent od RES-PUBL. BRYTANICA, Her Supplication? Which is, That, ΣΤΟΛΟΣΕΞΩΠΛΙΣΜΕΝΟΣ, may helpe us, not onely, to ΦΡΟΥΡΙΟΝ ΤΗΣ ΑΣΦΑΛΕΙΑΣ: But make us, also, Partakers of Publik Commodities Innumerable, and (as yet) Incredible. Unto which, the HEAVENLY KING, for these many yeres last past, hath, by MANIFEST OCCASION, most Graciously, not only invited us: but also, hath made, EVEN NOW, the Way and Means, most evident, easie, and Compendious: Inasmuch as, (besides all our own sufficient Furniture, Hability, Industry, Skill, and Courage) our Freends are become strong: and our Enemies sufficiently weake, and nothing Royally furnished, or of Hability, for Open violence Using: Though their accostomed Confidence, In Treason, Trechery, and Disloyall Dealings, be very great. Wherein, we beseche our HEAVENLY PROTECTOR, with his GOOD ANGELL to Garde us, with SHIELD AND SWORD, now, and ever.

Dee’s vision is clear. The Queen, at the helm of the imperial monarchy, which is identified as a ship, representing the most part of Christendom (labelled Europe), is being implored by the British Republic, to pursue a divinely sanctioned imperial destiny.

French notes that the naked figure she gestures to is opportunity. For Dee, a strong navy is the condition of fulfilment for the fate embedded in this composite image.

While the General and Rare Memorials is a public expression of Dee’s appeal to Elizabeth, his position in court enabled him to make a much more private and direct approach. The Limites, effectively lay out the case for Royal title to huge chunks of the globe, and it is clear how these justificatory tracts complement the appeal in the Memorials, entreating Elizabeth to go forth to meet her imperial destiny.

This excerpt from Trattner will serve to highlight Dee’s involvement with some of the important voyages of the period, which represent the very first steps in the establishment of a British overseas empire:

In spite of John Cabot’s early failure, in 1497, to reach Cathay by sailing west and north from England, the belief in a Northwest Passage around America persisted for many years. Englishmen sent voyage after voyage in this profitless and discouraging quest. The most recent examples of the search for the Northwest Passage were the three voyages of Martin Frobisher in 1576, 1577, and 1578. Dee was intimately involved in these attempts, dealing with the expedition both as a promoter and an official geographer. As a promoter he had subscribed some money to Frobisher but although a shareholder in the venture, George Parks is quite correct in maintaining that Dee’s “economic interest was in all likelihood a result and not a cause of his intellectual interest; he was probably adviser first and investor second.” As early as 1576, even before the writing of his General and Rare Memorials Dee had been called upon to give lectures in the art of navigation to Frobisher’s company.

At about this same time (1577-1580) Francis Drake was making his successful voyage around the world. There is strong evidence that Dee was also in the counsels of those responsible for that venture. The promoters of Drake’s voyage included the Earl of Leicester, Walsingham, a Court Secretary and leader of the colonial party, Hatton, and Dyer, all of whom were close acquaintances of Dee. And the earliest entries in Dee’s Private Diary refer to visits from Drake’s friends and backers at precisely this time.

By the year 1577 the active, restless brain of Humphrey Gilbert was at work on the problem of the exploration and colonization of America, and it is perhaps more than a coincidence that Gilbert called on Dee the day before he affixed his signature to the document entitled: “How her Majesty May Annoy the King of Spain.” On November 6th, 1577, Dee recorded, “Sir Umfrey Gilbert caim to me at Mortlak.” Shortly thereafter Gilbert was awarded a patent for his colonizing scheme in the New World. Only about three weeks later Dee was summoned to the Court to explain to both the Queen and Secretary Walsingham (who was behind both Drake’s and Gilbert’s voyages) her title to the land to be colonized. [Walter Trattner, ‘God and Expansion in Elizabethan England‘]

[At this point, a sidestep: in 1958, Carl Schmitt penned his Dialogue on New Space, which itself takes up some of the themes treated in a more robustly academic manner in The Nomos of the Earth. One such theme is the spatial opposition between the land and sea, and the subsequent distinction between terristrial and maritime exixtence. In his analysis, which seems heavy with a pathos and a nostalgia it would be interesting to try to unfold, he identifies the island nation of England as uniquely situated to respond to what he refers to as the ‘call’ of the epoch. Let us take a few quotations: The island England must have fulfilled a particular historical condition when the industrial revolution emerged precisely there and precisely in the eighteenth century. […] The idland England, on which the industrial revolution emerged, was really no random island. It underwent a very definite historical development and took an astounding step. It underwent the transformation from a terrestrial to a maritime existence in the immediately preceding two centuries. […] this people of shepherds metamorphosed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries into a people of sea-dogs. Now the island turns its countenance away from the continent and glances out upon the great seas of the world. It lifts anchor and becomes the bearer of power over an oceanic world empire. […] At that time, in the age of the great European discoveries, many able and even excellent peoples either did not heed the call of the oceans opening themselves or they did not follow the call or they followed it and yet finally remained upon the shore. The Spanish conquered an entire overseas continent, but they exhausted themselves in this great land appropriation, they became no oceanic sea people; they remained upon the soil of their traditional terrestrial existence.

And then on the relation between technological progress and maritme existence: We are speaking concretely of the industrial revolution that is our contemporary fate. It could not emerge anywhere other than in the England of the eighteenth century. An industrial revolution means the unleashing of technological progress, and the unleashing of technological progress is only comprehensible from out of a maritime existence. […] All that matters is what is made out of the technological inventions, and that depends on the frame, that is to say: in which concrete order the technological invention falls into. Within a maritime existence technological discoveries are developed more freely and with fewer restraints than when they are grasped and bounded. […] Technological discoveries are not revelations of a secretive higher spirit. They fall into their own time. They go under or they develop, according to the concrete human complete existence, into which they fall. I want to say this: the discoveries, with which the industrial revolution sets in, could only lead to the onset of an industrial revolution where the step toward a maritime existence had been taken.

When further questioned on this, the interlocutor (surely this is the Schmitt persona) responds with a metaphorics/metonymics of dwelling (Heidegger is again not far), opposing the house to the ship: You touch upon an immense theme. Today, I must satisfy myself by saying to you the following: the midpoint and core of a terrestrial existence – with all its concrete orders – is the house. House and property, marriage, family and hereditary right, all that is built upon the foundation of a terrestrial mode of being [eines terranen Daseins], in particular that of the agricultural farm […]. Thus, at the core of a terrestrial existence there stands the house. On the contrary, at the core of a maritime existence there sails the ship, which is already itself mush more a much more intensley a technological means than the house. The house is rest and the ship is movement. Even the space in which the ship moves is other than the space of the landscape, in which the house stands. In consequence, the ship has another environment and another horizon […]. The terrestrial order, in whose centre stands the house, necessarily has a fundamentally different relation to technology than a mode of existence, in whose centre a ship sails. An absolutisation of technology and of technological progress, the equivalence between technological progress and advancement as such, briefly, all that which allows itself to be brought together in the phrase ‘unencumbered technology’, develops only under the presupposition, only on the breeding ground and in the climate of a maritime existence. In following the call of he worlds oceans opening themselves and in completing the step toward a maritime existence, the island England gave a grand historical answer to the historical call of the age of discoveries. Simultaneously, however, it created the presupposition of the industrial revolution and the beginning of the epoch whose problematic we experience today.

If Schmitt’s thesis is assumed, a major assumption which can only be provisional in advance of a much deeper exploration, then a rough and ready reading might well situate Dee at the very origin of the response he speaks of. We have to admit, while acknowledging that the status of this ‘call’ is totally undefined and must be considered to not have an origin, this is highly seductive]

WORLDMAKING

When we look at Fludd’s diagram, it is as though we are looking through an apparatus, a kind of projector, organising, perhaps enframing, an encounter with the world. Let’s reread a quotation made from Heidegger above:

There begins that way of being human which mans the realm of human capability as a domain given over to measuring and executing, for the purposes of gaining mastery over that which is as a whole. [AWP, 132]

Earlier, we broke off the quotation at this point, but Heidegger continues:

The age that is determined from out of this event is, when viewed in retrospect, not only a new one in contrast with the one that is past, but it settles itself firmly in place expressly as the new. To be new is peculiar to the world that has become picture.

Dee’s manifesto, the Preface, which was such an inspiration to the organisation of Macrocosm II and the Fludd title image, and which itself, we saw above, constituted something of an event in Renaissance England, is delivered with all the evangelical fervour of an absolute novelty. What is new here is clearly not the interest in mathematics as such, but the expression of an applied mathematics which, extrapolated by a prophet/magus/philosopher like Dee, opens the prospect of an unprecedented control over the world, and fever dreams of global dominance, just as the globe was beginning to emerge as such. This dominance was viewed by Dee as a divinely sanctioned destiny, whose possibility opened as a unique historical opportunity.

However he sold it to himself, and others, there is no doubt that he was singularly struck by an imperative, and that he pulled on every lever available to him in its pursuit.

◊

The point of opening the HYPERDREAM with this reading of texts situated at two extremes of the modern period is not to simply endorse a particular reading of the modern, although I believe it is clear that, at a certain level of discourse, there is something inevitable about Heidegger’s analyses. It is rather to establish a means of approach. We have now reached a point of what might be called the full disclosure of the globe, or we are beyond it, but it is difficult to say what this means – and it is towards this question of meaning, of sense, that we are slowly making our way.

The HYPERDREAM is structured in three parts, each seeking to establish something about the event of globalisation, what Jean-Luc Nancy speaks of as the becoming world, or worldwide, of the world. The first section, SUNDOWNERS, is interested in the event itself, as something that happens to and by way of the West, at the moment it extends, exerts, exposes itself across the globe in its deconstructive achievement. It will have to explain itself on this privileging of the figure of the sunset, of the Occident. The EXCURSION ventures into the territory itself, while ON AUTONOMY, initially through a deeper reading of Nancy and Carl Schmitt, asks what a new NOMOS of the earth might look like, or how it is already beginning to emerge, after the event.

The PRELUDE, therefore, is preparatory for these later parts. It is a history of worldmaking whose dense networks of interwoven pathways (techno-, politico-, philosophico-, aesthetico- etc., etc.) cross and converge from this first exposure of the modern. We will set out again from Fludd’s diagram, but this time looking more closely at the specifics: the technics themselves. Beginning with the two techno-aesthetic categories of time and space, horology and geodesy.